The Problemist Diary - Part I

Welcome to the beautiful world of compositions and study solving. The problemist diary is an initiative by one of our regular readers Satanick Mukhuty. While we publish a lot of articles on improving your playing strength as a practical player with tactical, positional and endgame exercises, one thing we have realized is that having a keen interest in solving studies and compositions can really help you improve your imagination and creativity on the chess board. But doesn't the world of problem solving look daunting and difficult? Well, in the problemist diary series, Satanick will hold your hand and make you understand the basics of solving, the common terms and phrases used, with the final aim that you too, like him, will fall in love with the beautiful world of chess composing.

Art for Art's sake!

By Satanick Mukhuty

"Chess problems demand from the composer the same virtues that characterize all worthwhile art: originality, invention, conciseness, harmony, complexity, and splendid insincerity" - Vladimir Nabokov

A chess problem, also known as a chess composition, is a work of art in the guise of a puzzle. In simple words, it is a position set by a composer using pieces on a chessboard that presents before its audience a particular task to be realized. The construction of such a position happens in accordance with special artistic principles and the play of its solution manifests a striking chess theme or idea. Let us look at our first example to better understand the guiding motivation behind problem composition. The goal in the following case is simple, White is to play and deliver mate against any defences by Black within two moves. A problem like this, where White has to mate Black in a stipulated number of moves against any defences, is termed as a Directmate.

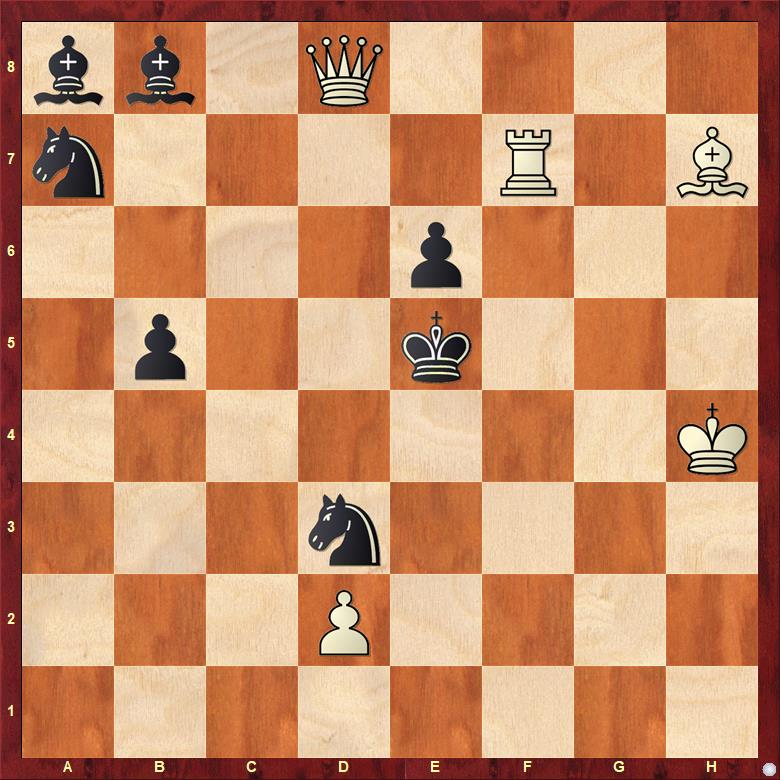

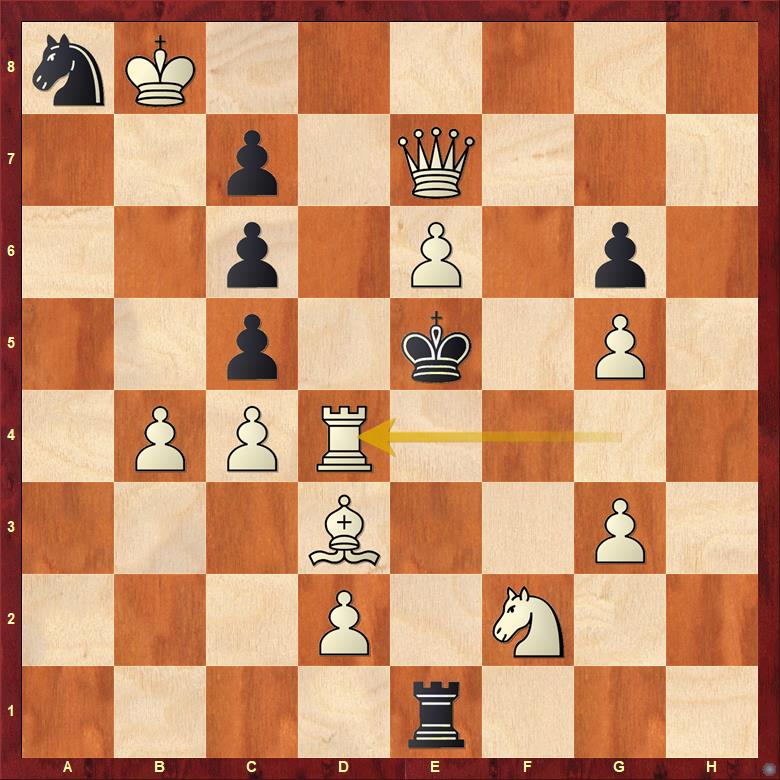

Problem 1

Thomas Henry Billington, Birmingham Weekly Mercury 1900, 1st Prize

The solution begins with the startling and sacrificial 1.Rf4! that puts the rook on an unguarded square controlled by two enemy pieces. White is threatening 2.Qd4# here, Black tries to defend against this in various ways but these only open up new weaknesses, allowing White to deliver mate in the stipulated number differently. For instance, 1...Bd6 stops 2.Qd4# but at the same time takes away a flight square from the black king, facilitating 2.Qg5# - this kind of fault that Black commits by placing his piece on his own king's escape square is termed as a self-block. This theme is echoed in another variation where Black goes 1...Bd5 preventing 2.Qd4# but meets 2.Qxb8# instead. 1...Nc6 and 1...Be4 are other attempts at stopping 2.Qd4# but these unguard the e4 square allowing 2.Re4# and 2.Rxe4# respectively. So far, so good but what if Black simply takes the undefended rook? Well, if 1...Nxf4 then comes the exquisite pawn-mate 2.d4# also by virtue of self-block, and if 1...Kxf4 then 2.Qf6#

Indeed, part of the romanticism of composition chess lies in its intensity. As Dr. Milan Vukcevich, an eminent scientist and a renowned chess composer, had once remarked, "Relative to the game, a good chess problem activates more force per move, uses pieces more efficiently and stresses more on their cooperation and interference with each other". The above problem demonstrates how closely contested the battle between the two sides can be even if it's only for two moves.

Replay the full solution with variations here:

One very important thing to note is that the key or the first move of the solution to a problem is always unique. In the above 1.Rf4 is the only move that solves the task. The existence of even one single alternative is sufficient to render a problem effectively useless. Why? Because additional solutions cheapen the value of the intended one, however pretty that might be in itself. A brilliancy is not much of a brilliancy after all if it is merely one of many available choices. Another significant convention with regards to the key move is that it should not be a check or a piece capture. In an adversarial problem all that a composer is trying to depict is the element of contest, an ideal problem therefore is one that leaves as many resources to the defending side as possible. A check on the other hand drastically reduces the number of options and the same goes for a capture that removes a whole piece from the board. But as we shall see in our subsequent articles, in longer problems or studies, where the post-key play holds sufficient interest, this "rule" is frequently violated. But still a composer will always prefer a quiet, subtle key whose point is well hidden rather than a brazen check, and that's how solving problems differ from solving tactical exercises where one is instructed to begin with looking for forcing moves in the form of checks and captures. In fact, while solving compositions expecting the unexpected often helps. The next problem brilliantly illustrates this.

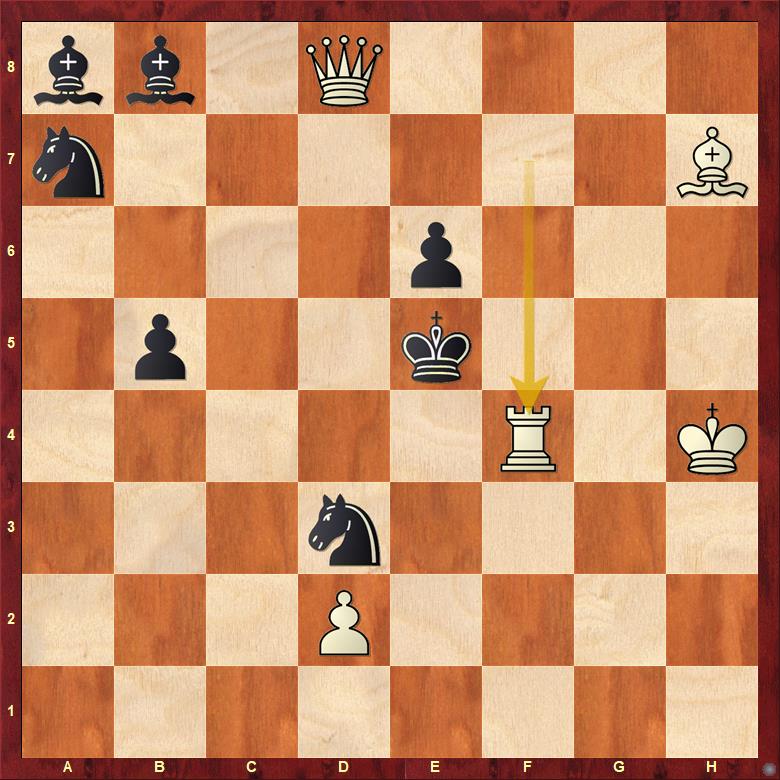

Problem 2

John Hugh Barrow, The Grantham Journal 1926, 1st Prize

Problem 1 had an exceptional key, in that it was giving up a whole rook to two enemy pieces. The present problem only builds up on this sacrifice theme, the solution begins with the bedazzling 1.Be5! giving the bishop up to four enemy pieces. Black is forced to accept the sacrifice as 2.Qd4# is threatened, the four possible captures give us the four variations of the solution. 1...Kxe5 is answered by 2.Qc5#, 1...Nxe5 by 2.Nf4#, 1...Rxe5 interferes with the bishop's line thus allowing 2.Rd1#, and finally with 1...Bxe5 the rook's line is interfered which gives 2.Be4# - the last two variations show what is known as a Grimshaw Interference: two linear pieces of the same colour (here, a rook and a bishop) with dissimilar movements interfere with each other’s line of action by playing in turn to a square where the two lines intersect. The Grimshaw Interference in this case is effected by a sacrifice, this is known as a Nowotny.

We understood a very important interference idea in the above problem. In the next problem, we see a key based on clearance theme. One would recall from lessons in basic chess tactics that a clearance refers to a deliberate sacrifice of material with the aim of freeing up a square or line.

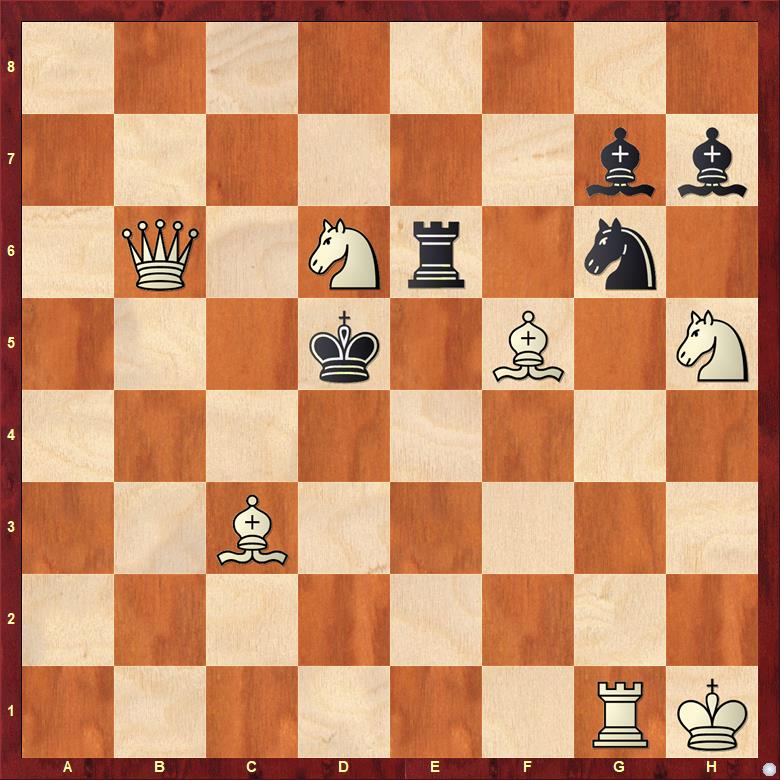

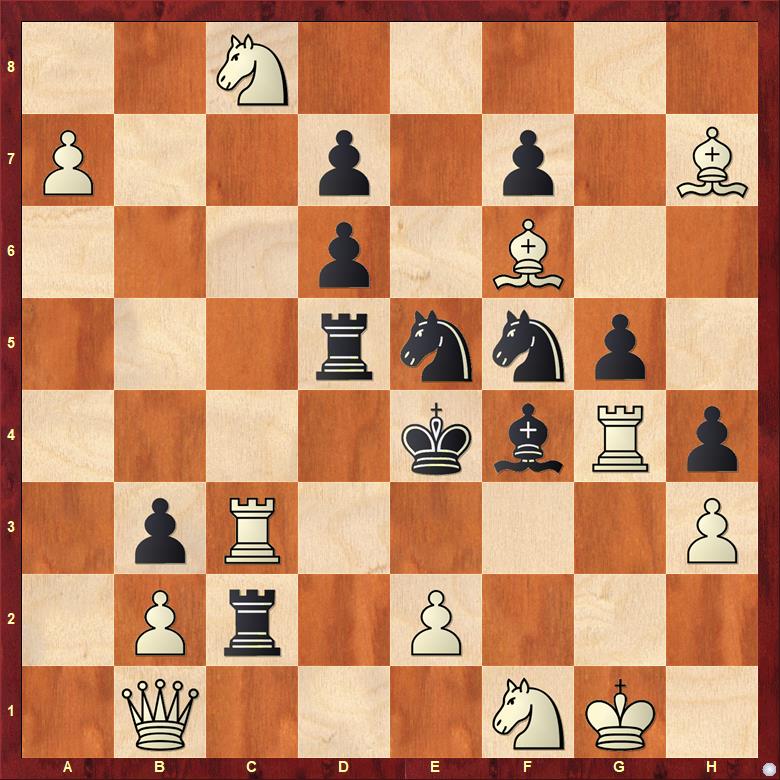

Problem 3

Valery Yuryevich Shanshin, ChessStar 2016, 2nd Prize

This problem reinforces the idea of uniqueness of key for there are a couple of moves here that come very close to meeting the stipulation but fails to unique refutations. These attempts are termed as tries, let's begin by examining them first. Try 1.Rf4 clearing up the g4 square and threatening 2.Ng4#, there's only one move that refutes this plan and that is 1...Re4!; try 1.Bf5 threatening 2.Qxc5#, now 1...Kxf5 is answered by 2.Qf6# and 1...gxf5 by 2.Nd3# (clearance, self-block), but there's 1...Nb6! that refutes; try 1...Bxg6 again vacating the d3 square and threatening 2.Nd3# but there's 1...Re3! So what should be the solution? Well, we have eliminated all the tries that involve clearance, the key move isn't hard to guess anymore, it is 1.Rd4! clearing the g4 square. Now 2.Qf6# is threatened, hence Black has to take the rook. If 1...cxd4 then 2.Ng4# and if 1...Kxd4 2.Qxc5#

Going through these problems, an over-the-board player might frown upon the set-ups. None of these look practical! Well, as we have mentioned in the beginning of this article, chess compositions are designed in accordance with their own artistic principles with the sole aim of expressing a beautiful chess idea. They therefore don't have to conform to a player's narrow sense of practicality. But however these positions have to be legal. That is, it should be theoretically possible to achieve them from the initial game-array through a legal sequence of moves. The above positions, no matter how bizarre, are all legal. Does solving such positions improve one's game? Well, it is difficult to quantify art in such materialistic terms. Chess compositions have their own intrinsic value, independent of whether they take from or add to a player's capacity for the game, and that's what we are hoping to establish through this series of articles.

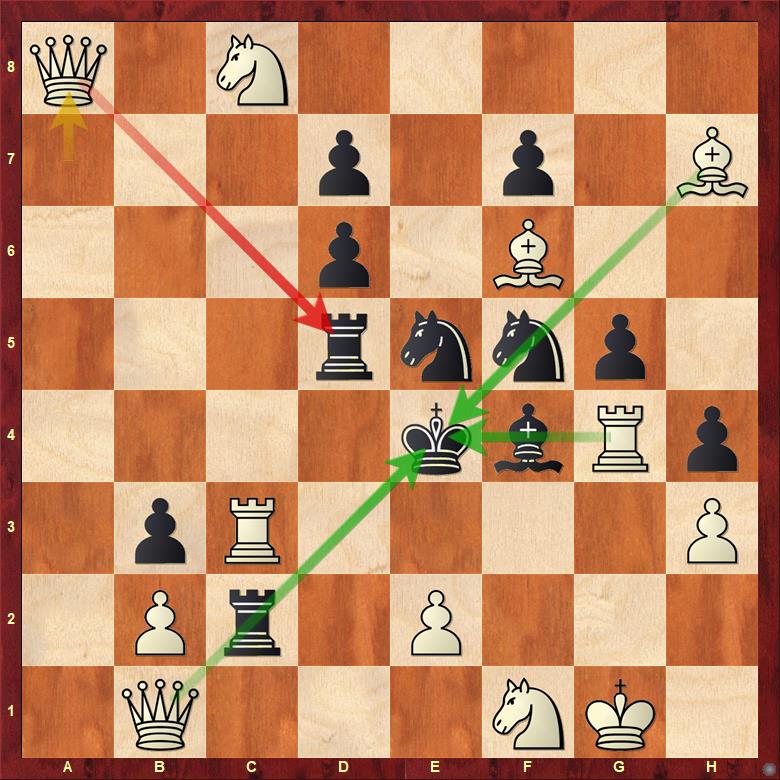

Problem 4

Fadil Abdurahmanović, Match Netherlands - Yugoslavia 1985, 1st Place

The above portrays a complex situation where many pieces are clubbed together against each other. However, a careful look reveals a striking point. Three of Black's pieces - Rc2, Nf5, and Bf4 - are incapacitated by pins. The key move is 1.a8=Q, an unlikely promotion at the corner of the board that pins a fourth piece!

Black is in a zugzwang, the only pieces he can move are the knight on e5 and the king on e4, wherever they go a mate awaits! The variations are: 1...Kd4 unpins f5 but ends up pinning e5 2.Qa4#; 1...Nc4 2.Rxc4#; 1...Nd3 unpins the rook on c2 but 2.Nxd6#; 1...Nxg4 unpins the bishop on f4 but 2.Rc4#; 1...Ng6 unpins the knight on f5 but 2.Nd2#; 1...Nc6 unpins the rook on d5 but 2.Re3#; 1...Nf3+ 2.exf3# - an intricate sequence of pinning and unpinning happens! Notice how the checkmates at the end of each variation is due some of Black's pieces being pinned, this effect is termed as a pin-mate - a widely explored theme in problems.

The position in the above problem is as far removed from game-like set-ups as imaginable. But one must notice that each of the units placed on board has a role to play, either actively by getting involved in the variations, or passively by stopping cooks or alternative solutions. This is another important artistic principle (of economy) that composers obey and strive to achieve. Each piece must have some definite role, preferably multiple roles; and the amount of force utilized must be minimized. For instance, a rook shouldn't be used for what can be done using a knight.

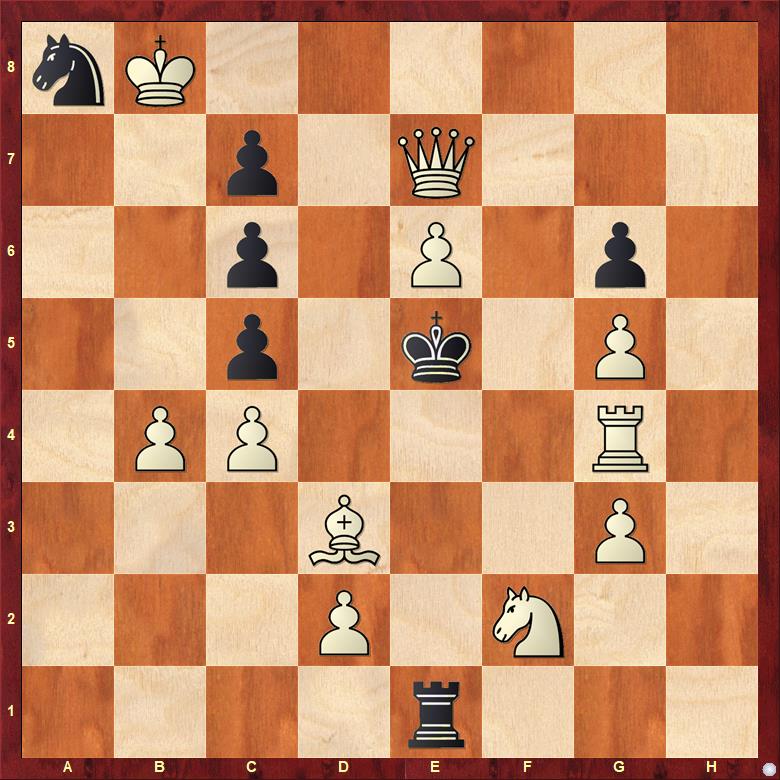

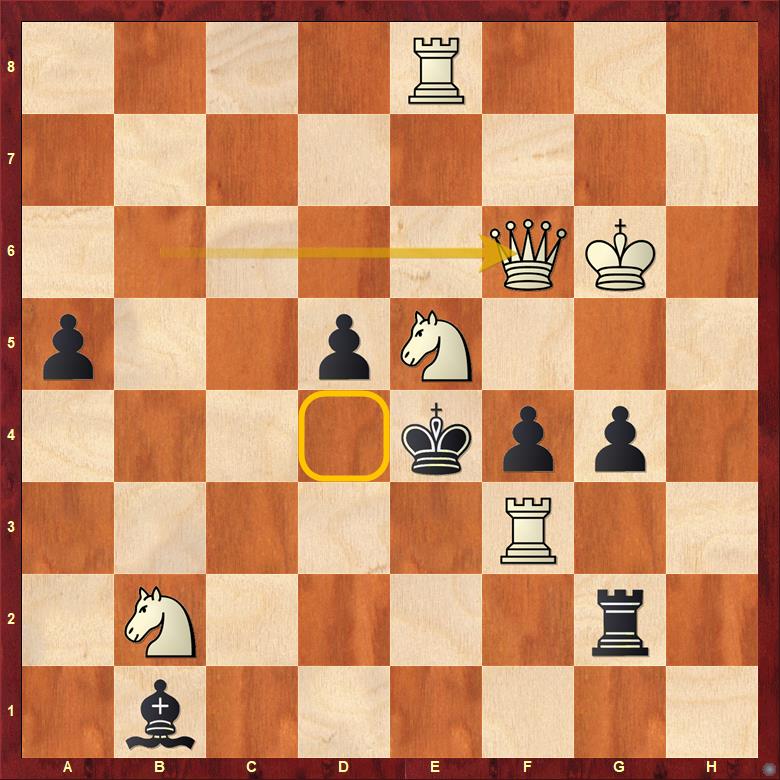

Problem 5

Luciano Borgatti, De Problemist 1929

The last problem of this article shows what is known as battery-play. A battery refers to an arrangement of two pieces, a rear piece and a front piece, such that when the front piece moves the rear piece delivers a "discovered" check to the opposing king. In the above position there are three batteries - along the e-file, the b1-h7 diagonal, and the g-file. The solution begins with the move 1.Qf6! threatening 2.Qxf4#.

In the variations the batteries play out: 1...d4 2.Qc6#; 1...Kd4+ 2.Nd3#; 1...g×f3+ 2.Ng4# - in the last two lines Black's checks are replied by counter-checks which come with mates - such tactics, where check is responded with another check, are termed as cross-checks. This problem nicely demonstrates a combination of cross-checks with batteries!

Play out the solution here:

About the author

Satanick Mukhuty is an author and social media manager at ChessBase India. He has a background in Mathematics. He is an avid enthusiast of composition chess and is sincerely committed to promoting it around the world.