Intellectual Fireworks—A Glimpse into Mumbai's Diwali Chess-Solving Spectacle!

ChessBase India's week-long, free-for-all Big Diwali Chess Camp concluded on a high note on October 27, 2024, after catering to nearly 500 enthusiastic attendees. On October 26, the penultimate day, an intense chess-solving contest took centre stage. The challenge was to solve six complex chess compositions in just two hours. Carefully curated by Satanick Mukhuty, the Chess Composition Editor of ChessBase India, the tasks included four problems and two studies designed to push the participants' strategic and tactical prowess to the limit. Ultimately, among the 35 contestants, the 22-year-old Pushkar Dere secured a decisive victory with a remarkable score of 29/30, outpacing the competition by a commanding 16.5-point margin. FM Vedant Panesar took second place with 12.5/30, closely followed by a four-way tie for third between Mitali Naik, Pratyush Bhatt, Arjun Iyer, and Neemay Bhanushali, each scoring 10/30. In this article, Satanick shares his insights into the contest and walks you through the solutions to all six challenging puzzles.

Chess-Solving: A New Sport?

Whether it's Arjun Erigaisi reaching 2800 Elo or Gukesh D vying for the World Championship title, India dominates the chess headlines these days. There is no denying that the country is witnessing a renaissance in chess terms. Yet, amidst this widespread craze, an intriguing facet of the game remains hidden in the shadows: chess composition and solving. Unlike Europe, where chess composition has flourished for decades, giving rise to esteemed societies and prestigious National solving championships, India's scene is still in its nascent stages. To bridge this gap, ChessBase India is taking the initiative to popularise solving competitions in Indian chess by incorporating them into mainstream tournaments and training camps. We hope to cultivate essential chess skills while fostering a broader culture of creativity, logic, and critical thought through chess composition.

Earlier this year, we brought this concept to life with inaugural chess-solving competitions in Bhopal and Hyderabad, alongside our regular blitz and rapid tournaments. The lack of expertise or experience was no barrier; the participants' enthusiasm more than made up for it.

Thus, encouraged by the response of over 200 players in the two cities, we decided to expand our chess-solving initiative to Mumbai, aligning it with our Big Diwali Chess Camp at the Phoenix Mall, Kurla. Due to space limitations, we capped participation at 35, filling spots on a first-come, first-served basis. And within hours of the announcement, all 35 spots were snapped up—speak of enthusiasm!

The contest itself yielded some unusual results. As mentioned, I chose six positions for the occasion (each worth 5 points), which I deemed moderately challenging. However, while the winner, Pushkar Dere, a player rated over 2200, scored an impressive 29 out of 30, most participants had difficulty solving even a single problem correctly. Notably, FM Vedant Panesar, the highest-rated player in the competition with an Elo rating over 2400, scored only 12.5 out of 30, underscoring how the skills needed for playing are somewhat different from those required for solving problems; being strong in one does not guarantee success in the other.

So, let's begin with the basics then. What is a solving contest? Well, it's akin to a math test. You are handed a sheet with a few chess positions to solve in a fixed timeframe. But here is the catch: these positions are not from actual games. They are chess compositions — positions ingeniously crafted to showcase distinct thematic or artistic ideas. Thus, for each position, the solver's task is to identify the specific idea the composer intended to convey. Precision is paramount in solving. In a tournament game, if you make a mistake, there's a possibility your opponent might overlook it or make an error themselves, giving you a chance to recover. However, when tackling a problem, you can't rely upon such oversights. The position has been carefully designed and tested with a computer program to be accurate — there is always only one correct answer!

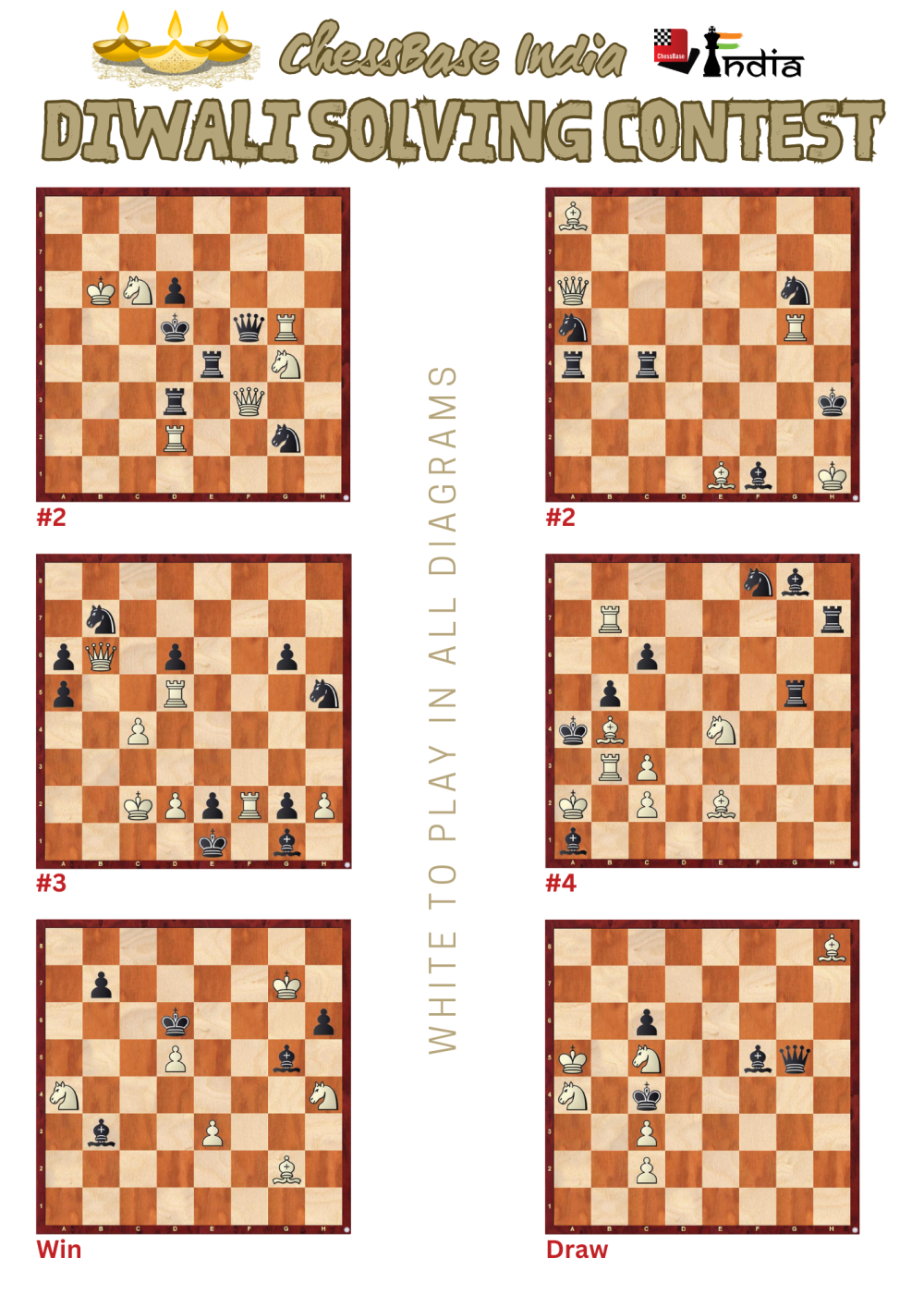

Now that we have laid the groundwork, we present the sheet with the six positions given to the participants. We recommend you time yourself and try to solve them on your own before scrolling down to the section with the solutions.

The Solutions

The first two of the six positions were mate-in-2s (two-movers). Here, solvers can score 100% by finding just the key moves. No variations are needed. The guideline for mate-in-n problems, in general, is to write the key along with all full-length variations till the penultimate move, i.e., the (n-1)th move. The final mating move in each line need not be mentioned.

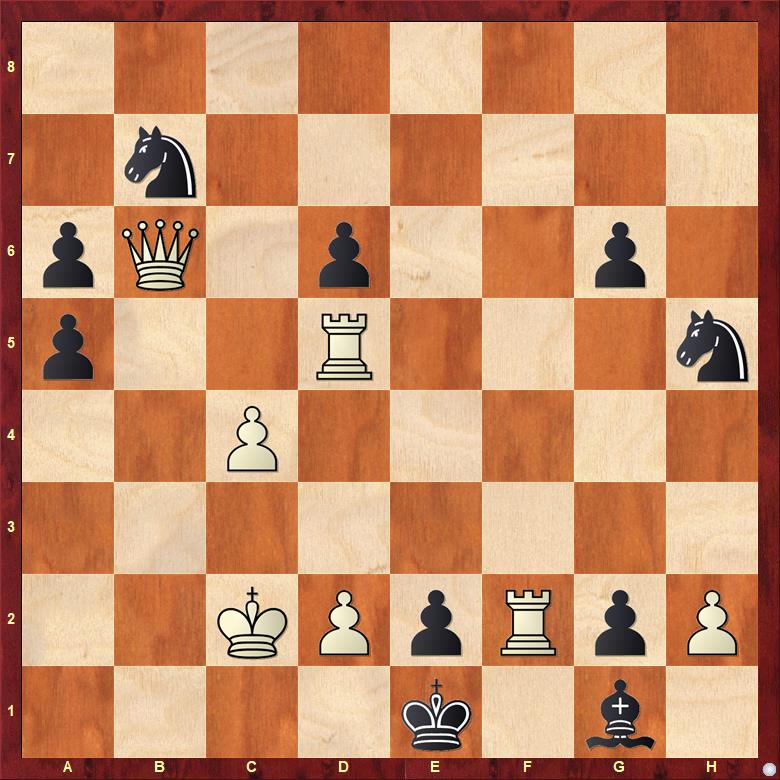

Problem 01

William A. Langstaff, Good Companion 1924, 2nd Prize

Curiously, Black has all three of their major pieces pinned in this one. The key 1.Nf2! exploits this situation, threatening 2.Qxe4#. 1...Rdd4 parries the threat but interferes with the e4 rook's path on the 4th rank, enabling 2.Qb3#. Similarly, 1...Qe5 blocks e4-e6, facilitating 2.Qf7#. Two more variations arise if Black's king moves: 1...Kc4 2.Qxd3# and 1...Ke6 2.Qxf5#. Note that, in the competition, you only had to mention 1.Nf2 to earn the full five points. Now onto the next problem...

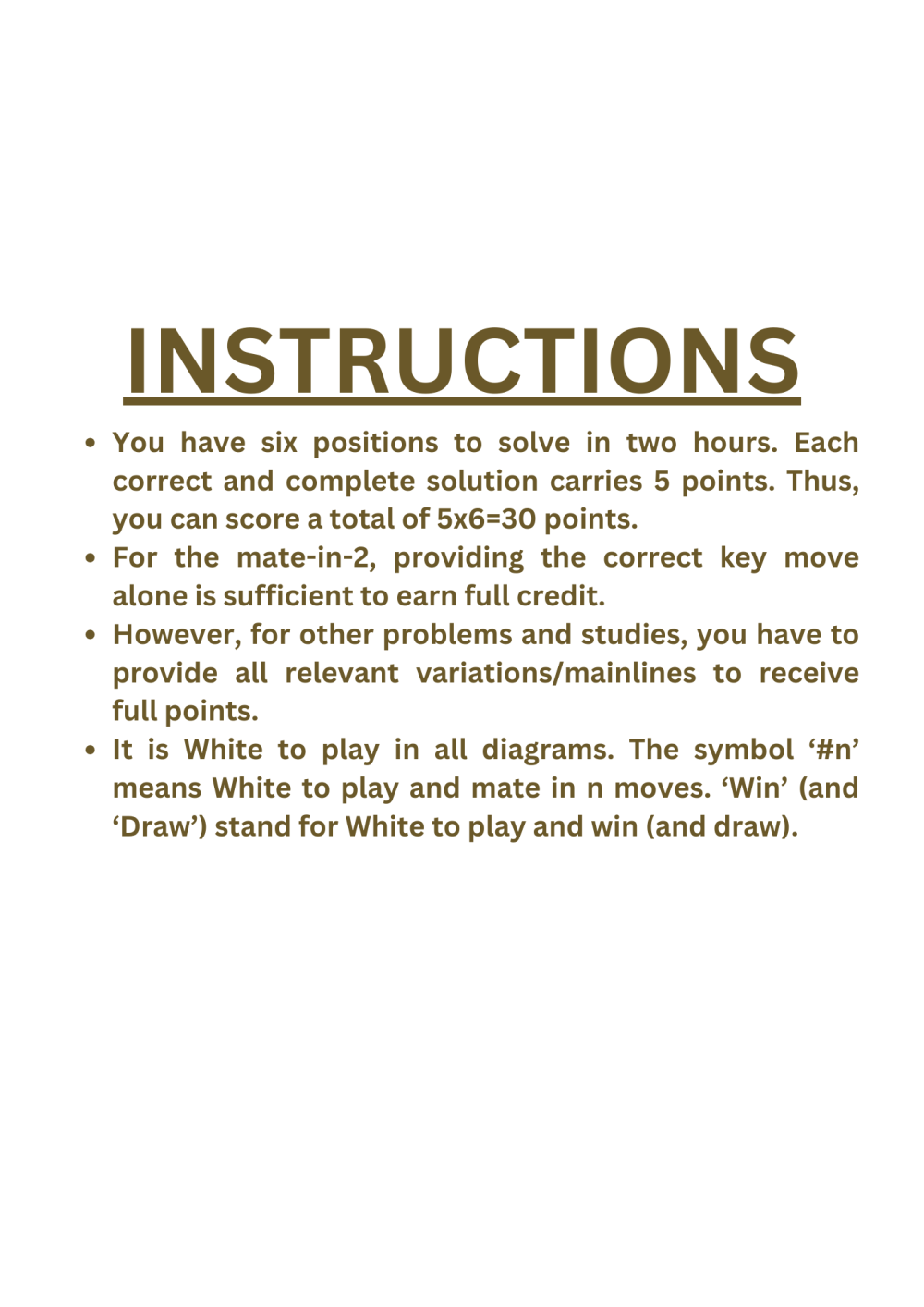

Problem 02

Jan Hartong, Schakend Nederland 1966, 1st Prize

This one is a little more creative than the last. Imagine if there was no rook on c4, simply Qxf1 would be checkmate then, right? Observing this leads you to the key move: 1.Be4! By cutting off the rooks on the fourth rank, White threatens 2.Qe6#. Of course, 1...Rc6/Rc5/Rxe4 are now met with 2.Qxf1#. The other variations are 1...Bg2+ 2.Bxg2#, 1...Be2 2.Bg2#, 1...Nc6 2.Qc8#, 1...Ne5/Ne7/Nf8 2.Qh6#, 1...Nf4 2.Bf5#, and 1...Nh4 2.Rg3#. Once again, mentioning only 1.Be4 gets you 5/5. It is assumed that you have seen all these variations when you have found the key!

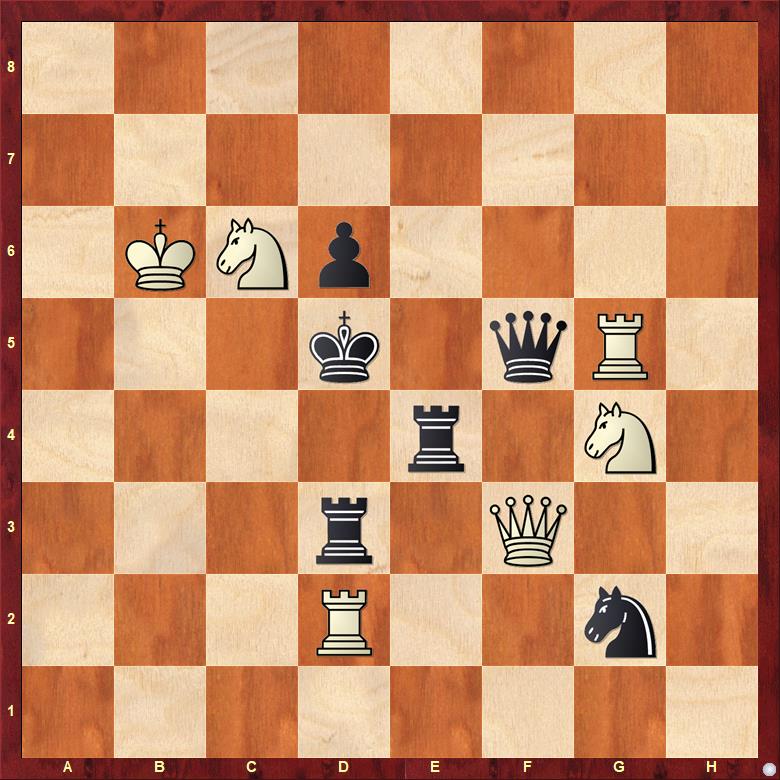

Problem 03

Joseph Warton, BCPS Ring Tourney 1967, 2nd Prize

Joseph Warton (and his brother Thomas) were quintessential puzzlers. They cared little about the "art" of chess composition; most of all, they wanted to trick solvers! This three-mover is a fine example of their style. Would you expect 1.Rc5!, blocking the queen's line, to be the key move here? This actually sets up the threat: 2.Rf3, followed by 3.Qb1#. Now 1...Kxf2 runs into 2.Rf5+! followed by 3.Qxg1#/Qb1#. And 1...Nf4 is simply met by 2.Rxf4!, after which 3.Qb1# is imminent.

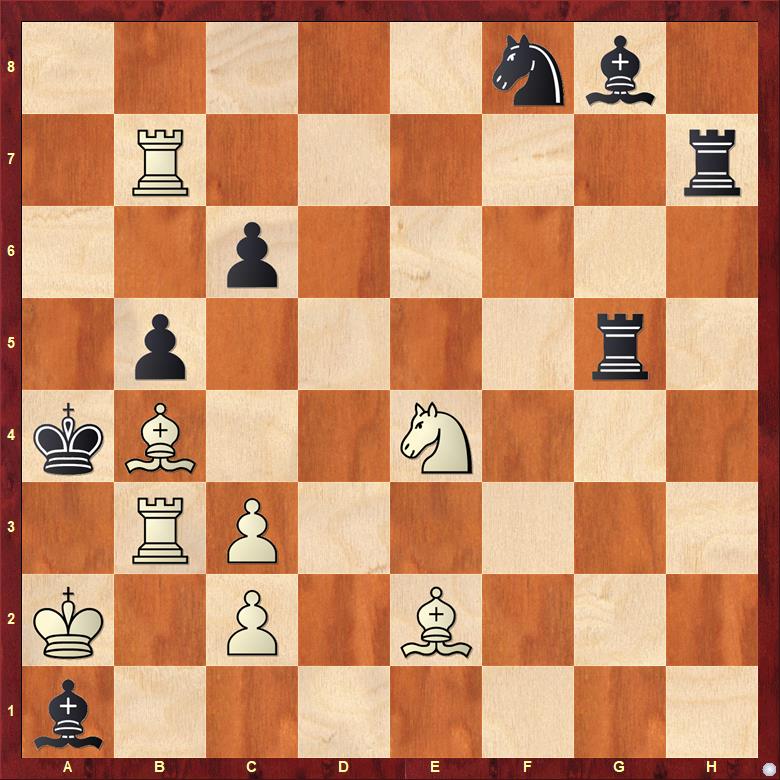

Problem 04

Rafael Ruppin, Problem (Zagreb) 1960, 1st Prize

Now we enter more serious, artistic territory! Were the b3 rook not pinned, Rb3-a3 would be instant mate in 1. Thus, White devises a clever plan to unpin the b3 rook by luring one of Black’s rooks on to the g8-a2 diagonal.

The solution begins with 1.Kb1!, threatening 2.Ra3#. And now 1...Bxb3 runs into 2.cxb3+ Kxb3 3.Nd2+ Ka4 4.Bd1#. Therefore, Black’s main recourse is checking the wK on the first rank, resulting in the following thematic variations:

1...Rg1+

2.Bd1! Rxd1+

3.Ka2 threat: 4.Nc5#

3...Rd5 4.Ra3#

And

1...Rh1+

2.Bf1! Rxf1+

3.Ka2 threat: 4.Ra7#

3...Rf7 4.Ra3#

The thematic sacrifice of the bishop, first on d1 and then on f1, ensures Black's rooks unfavorably block the g8-a2 line. With 3...Rd5 and 3...Rf7, though the rooks defend against the immediate mate threats Nc5 and Ra7, they also unpin the a3 rook in the process, enabling Ra3#. This idea is known as the Roman decoy and can be formally defined as follows: A black piece, initially defending effectively, is relocated to a new square where it still defends, but incurs a crucial weakness, which White then exploits.

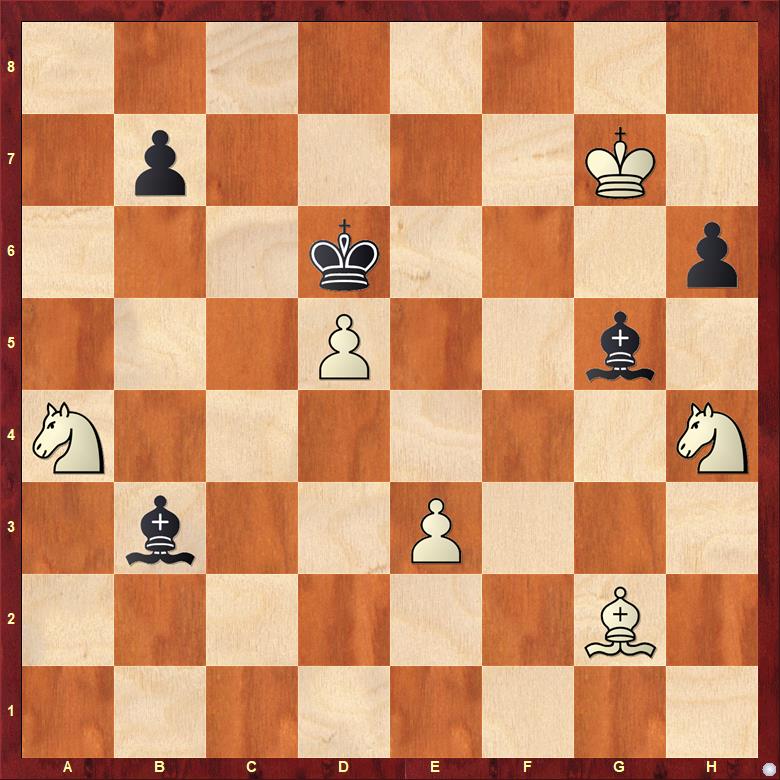

Problem 05

H. Grondijs, Foguelman-95 MT 8th UAPA internet tourney 2019, 2nd Commendation

White is up a piece, but both their knights are en prise, and it looks as though Black is about to equalise, grabbing some material…or not!

1.Nf5+ Ke5

A draw seems on the cards now via Bxd5 Kxd5 Nxb7 Bxe3, but White has something else up their sleeve!

3.Nd3+! Kxf5

4.e4+! Bxe4

5.Bh3#

Of course, something like 4…Ke6 5.exd5+ Kd6 6.Kg6 allows White to gain back the material and secure a winning endgame.

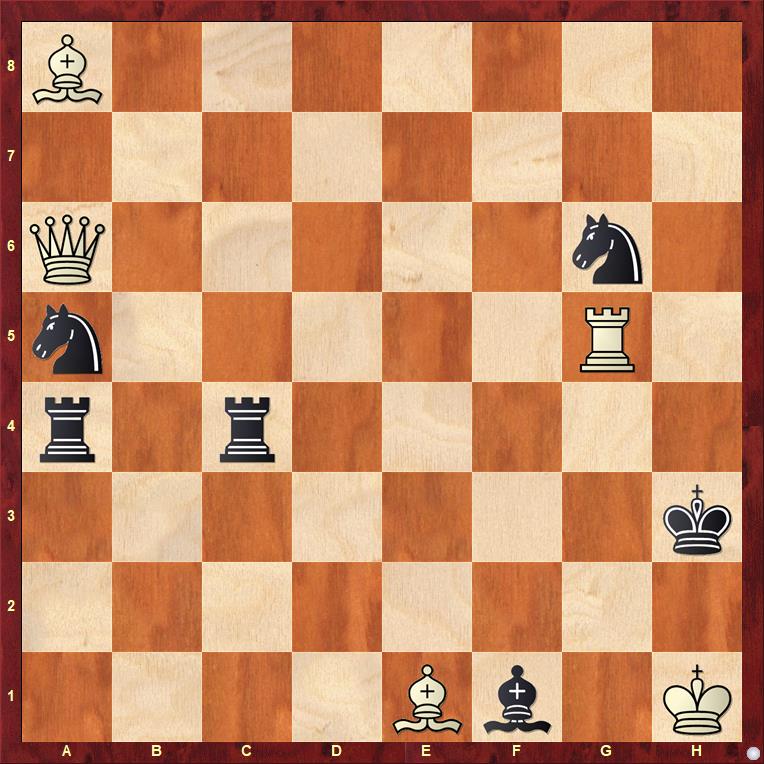

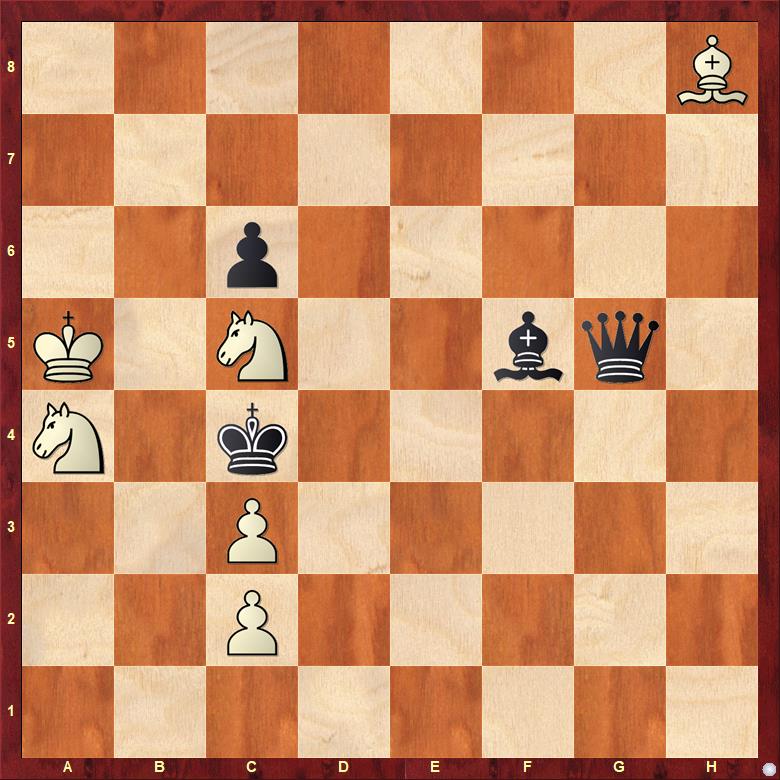

Problem 06

Leonid Kubbel, Listok Kruzhka Petrogubkomunni, 1921

With Black’s queen still on the board, a draw seems improbable. But astonishingly, White forces a stalemate from this position in just four moves.

1.Bf6!

1.Bd4, threatening Nb6#, fails to impress, as the simple 1…Kd5 maintains Black's edge.

1...Qxf6

Taking the bishop is almost forced. Other moves lose the queen:

1...Qe3 2.Nb6+ Kxc5 3.Bd4+

1...Qd2 2.Nb6+ Kxc5 3.Be7+

2. Nd7! Bxd7 — Yet again, Black must capture on d7 in view of the double threat: Ndb6# and Nxf6!

3.Nb6+ Kxc3

3...Kc5 4.Nxd7+ Kc4 5.Nxf6= is a prosaic draw.

4.Nd5+! cxd5, and just like that, it’s a stalemate!

Photo Gallery

_XHXQ6_1000x563.png)