How to Compose an Endgame Study: A Step-by-step Guide

The chess world is awash with resources for players looking to up their game, from countless articles and books to videos. Although relatively scarcer, a wealth of instructional material also exists for those interested in chess solving. But few have ventured to teach how to compose a chess study or a problem—no definitive course or authoritative guide for this aspect of chess. Yet, like playing and solving, composing, too, is a teachable skill—or at least that is what Gady Costeff, the writer of the present article, believes. To put his notion to the test, he demonstrates how to craft an endgame study by starting with an attractive mate position and then working backwards, guided by a series of straightforward questions and answers.

What Makes a Study Beautiful?

In Secrets of spectacular Chess, authors Friedgood and Levitt list four main categories:

Paradox: Sacrifices, under-promotions, drawing while down a queen, losing a tempo on purpose, creating a fortress position, are paradoxical because they break the rules that more material, more time, more space, are always better. Paradox is created when reality refutes our perception.

Depth: The more hidden the reason for a move, the greater its impact. Mysteries are compelling because to make sense of the world, or a study, we want to understand why a move is played. The more mysterious a move, the more interesting it is.

Geometry (pattern): We are wired to look for patterns, since recognizing them allows us to understand more of the world. The sun’s route from east to west, the chorus in a song, or the alternating color of the knight’s movement on the chessboard all encode a great amount of information. The same is true in studies. The relationships between pieces, moves, maneuvers, plans, or ideas, sometimes follow a pattern that provides a higher-level understanding of the study, beyond a sequence of moves.

Flow: Flow conjures a river that meanders over a long distance until it pours into the sea. An obstacle in the river, like a sunken barge or a dam, decreases the flow. In studies, the dam or barge are represented by captures. The less captures the greater the flow. The appeal of flow lies in the achievement of the goal with quiet means, using maneuvers rather than blunt force. However, it is harder to achieve paradox without some interruption of the flow.

Summary: paradox, depth, pattern, and flow occur with different intensity in all studies. It is helpful to know this terminology, but it is not crucial for composing a study.

Impact: The impact of a study can be roughly described as the ratio of beauty to material. The more beauty we pack into the study and the less material we use, the greater the impact of the study. Impact is the best measure of the study. A high impact study will make you go wow!

Before You Start

You will need a chess engine such as Stockfish, and you will need to know how to set up a position. This can be done easily using software on your phone or computer. Alternatively, you can set up your position on lichess.org/editor and then click on analysis board and the engine will analyze your position.

It is possible to compose without such help, but you need to be at least 2200 Elo, and even then, you will waste significant time by making analytical mistakes.

Let's Compose a Study

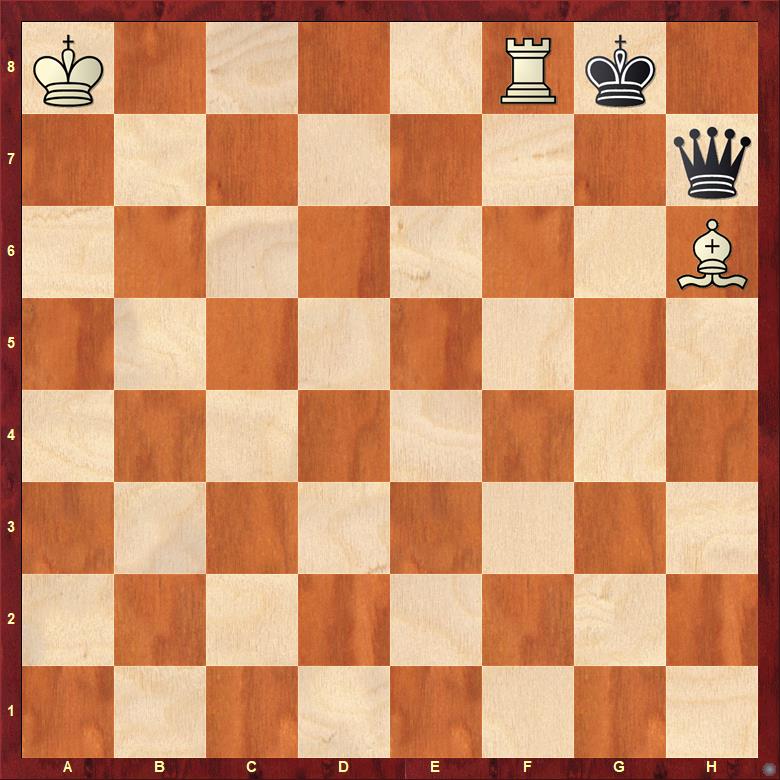

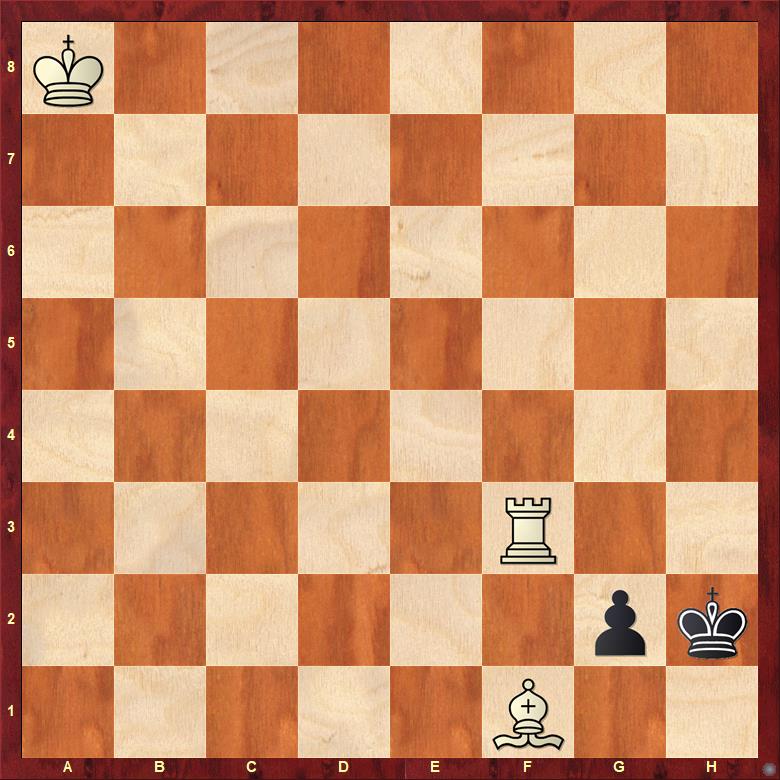

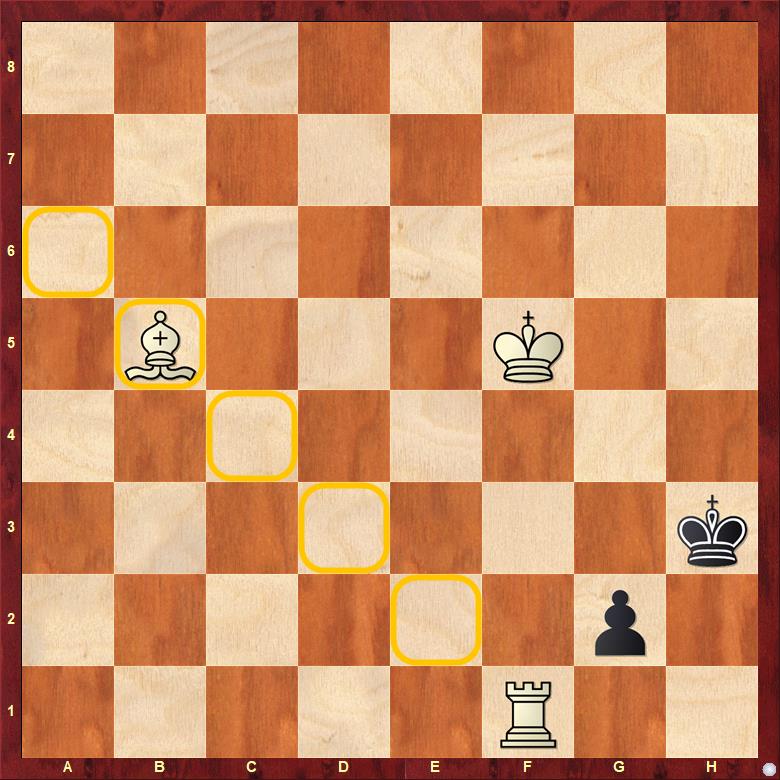

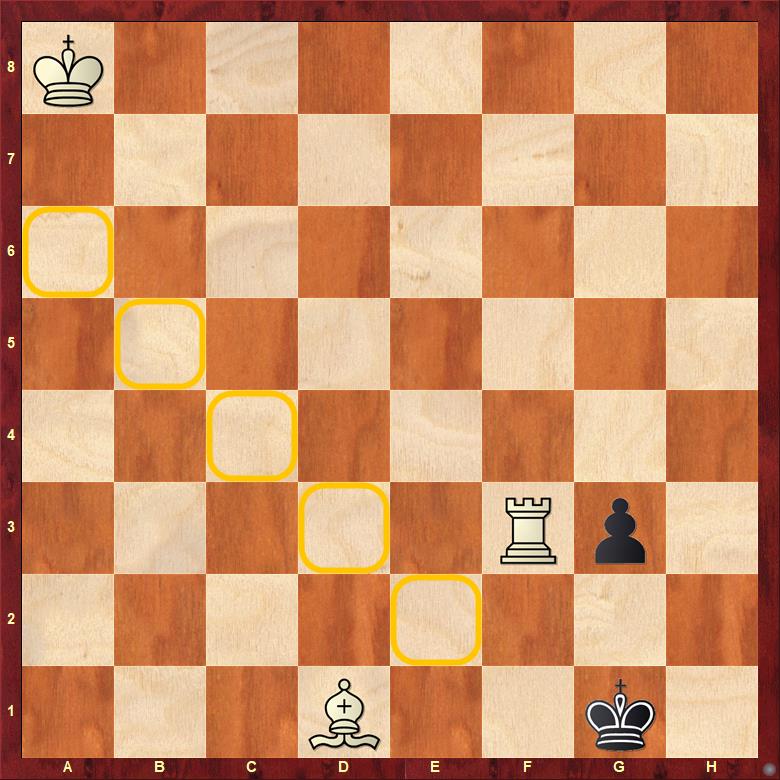

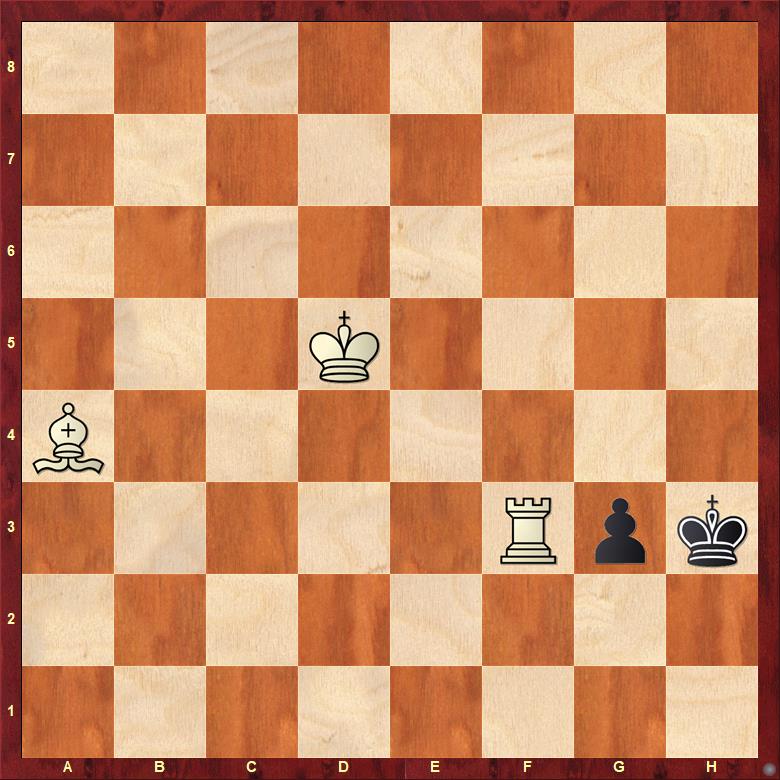

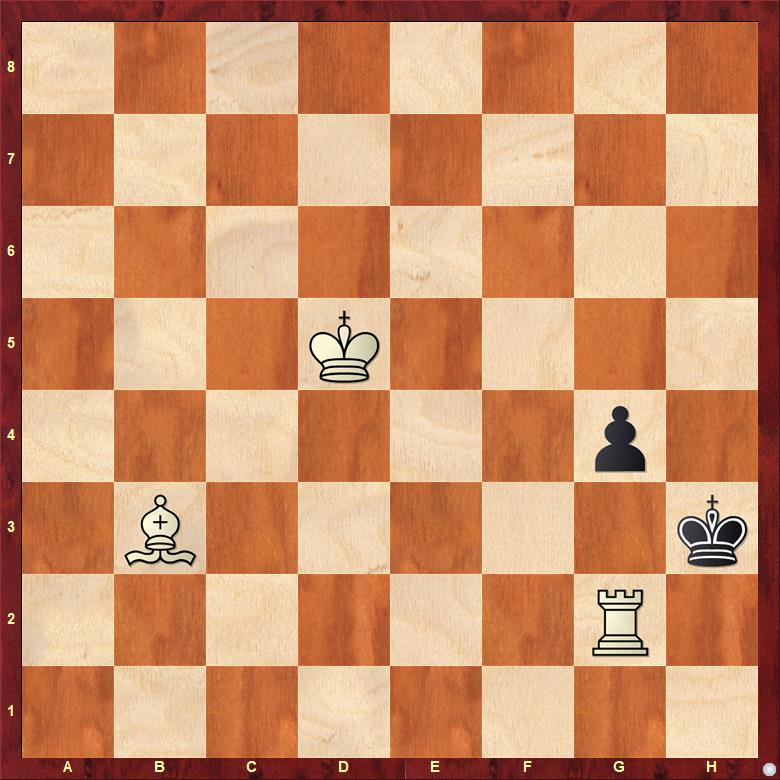

Every diagram below has a question, or two, which you need to answer. There are 27 questions in all. You can rate yourself by awarding 1 point for every correct answer. At the end sum up your score to find out your level. My First Endgame Study requires a study that ends with mate. To simplify matters, we will exclude the possibility of captures. Diagram 1 is our starting point.

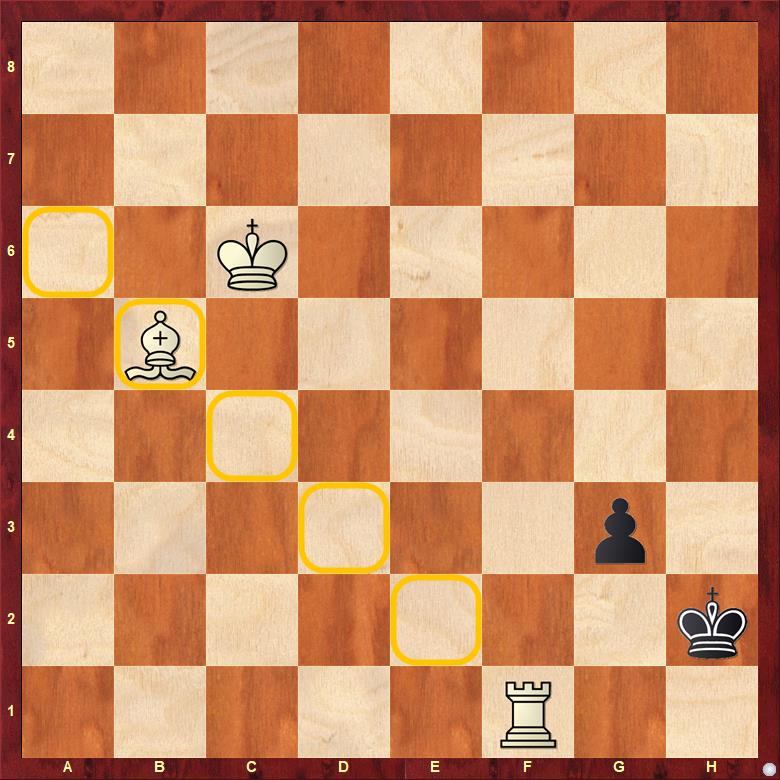

1.

Q1) What was White's last move?

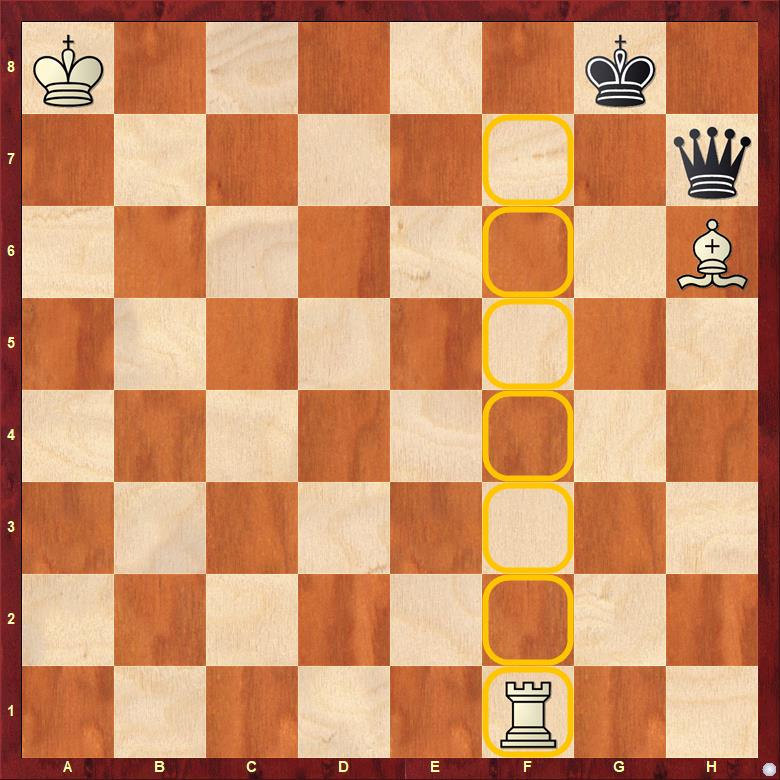

Remember, no captures are allowed. For Rf8 to be mate, the rook must come from one of the highlighted squares below.

2.

Q2) What was Black's last move?

Whether Black moved with king or queen, it was a blunder that loses the game to immediate checkmate instead of drawing or even winning.

Q3) Is there a non-capturing move for Black that achieves our goal? Hint: it requires thinking with the entire board in mind!

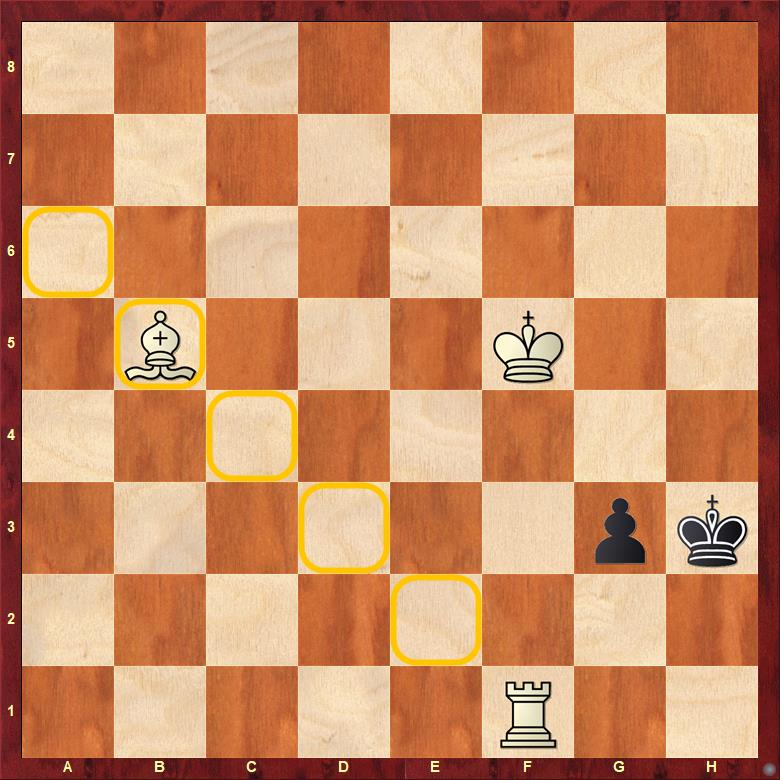

3.

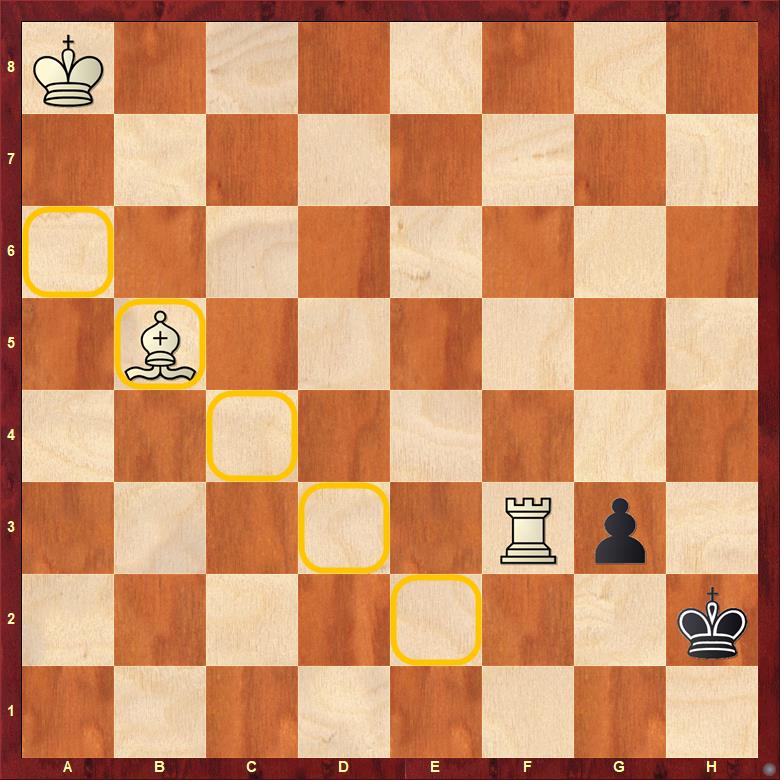

Q4) What was Black's last move?

4.

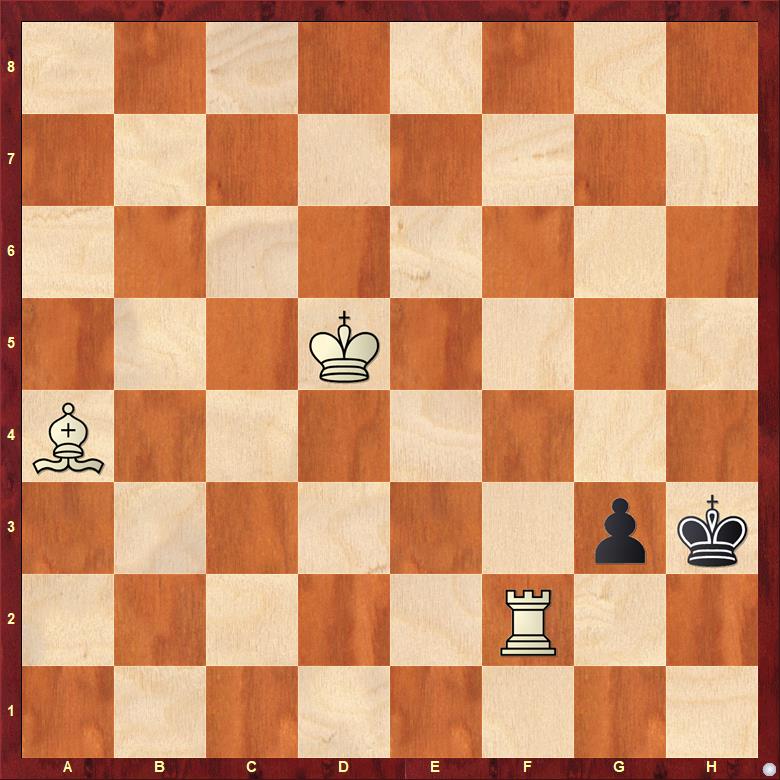

Now we have the possibility of 1…g1=Q 2.Rh3, reaching our desired mate. However, Black can play 1…gxf1=Q and win the game. A move that refutes the stipulation is called a cook.

Q5) Can we change the piece placement to eliminate this cook?

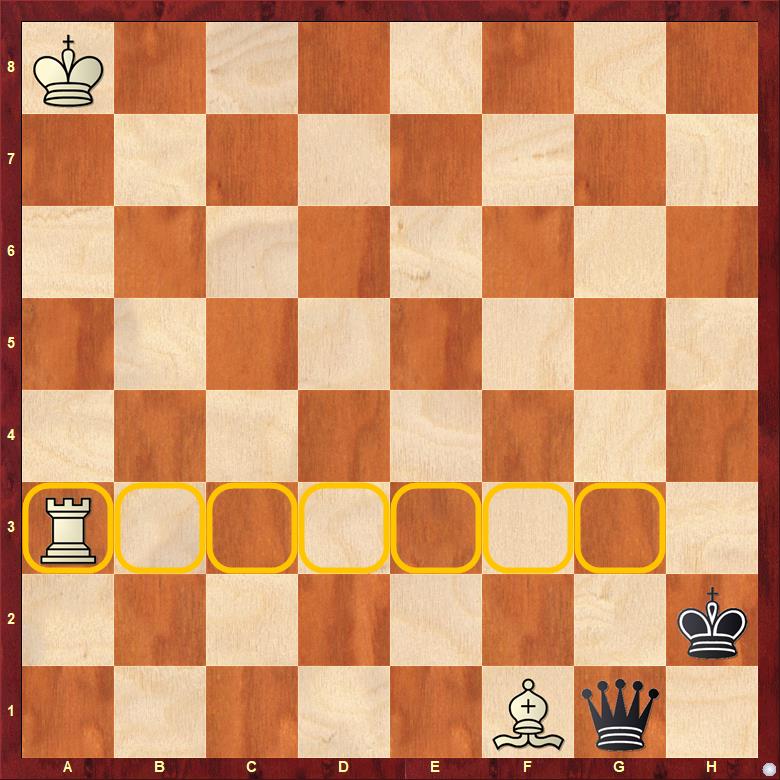

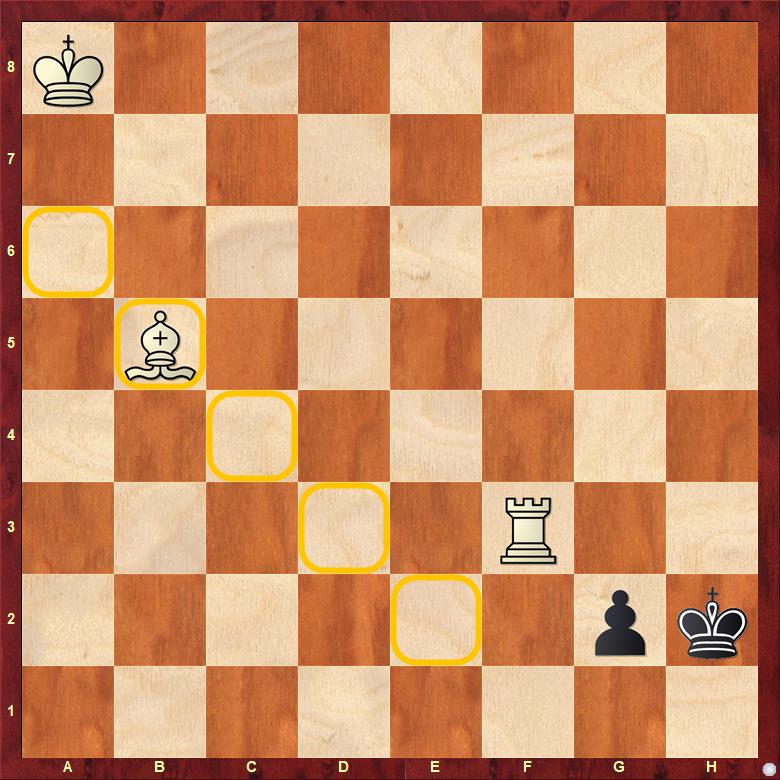

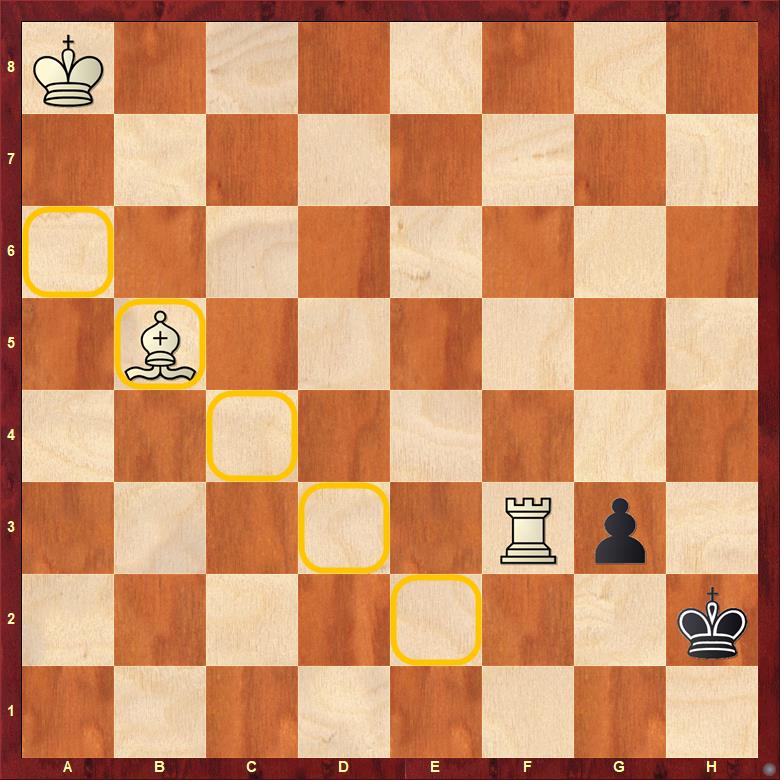

5.

Q6) What was White's last move?

If the rook or white king played the last move, then he would have had an alternative win with Bxg2. This is called a dual and ruins the study just like a cook. If the rook came from g3, then Rxg2+ would be a dual. Therefore, white’s last move was Bf1.

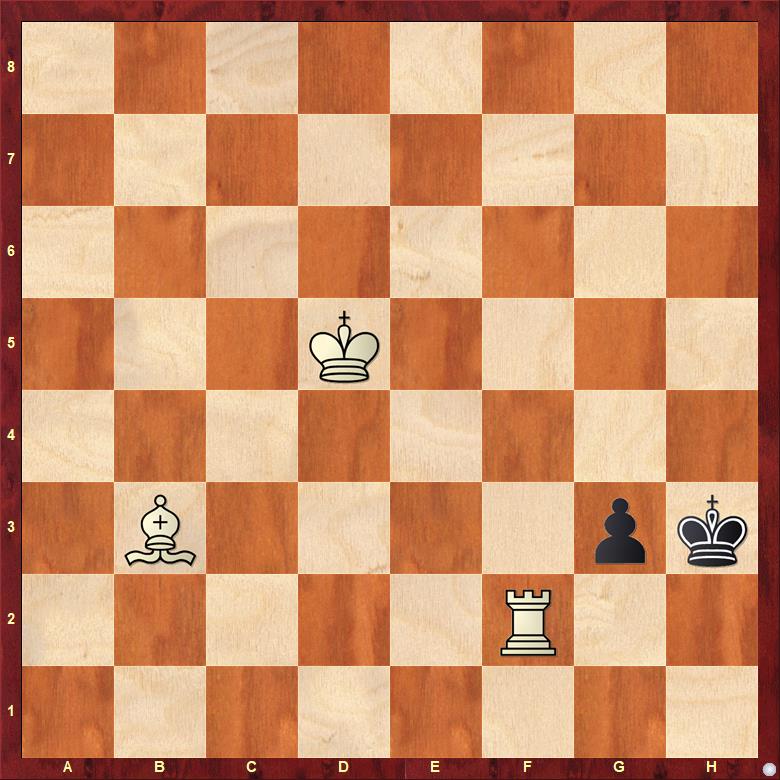

6.

Bb5, Bc4, and Bd3, are equally good choices but Ba6 limits the bishop. In this exploratory phase, we want to keep as many options open as possible.

Q7) What was Black's last move?

There are 3 possible last moves:

A) 1…Kh3-h2

B) 1…Kg1-h2

C) 1…g3-g2

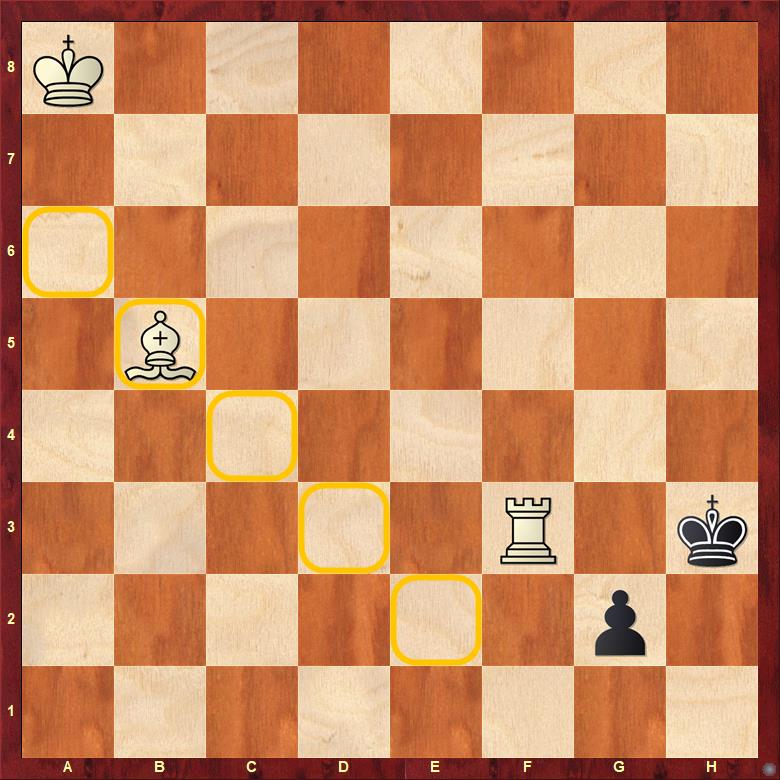

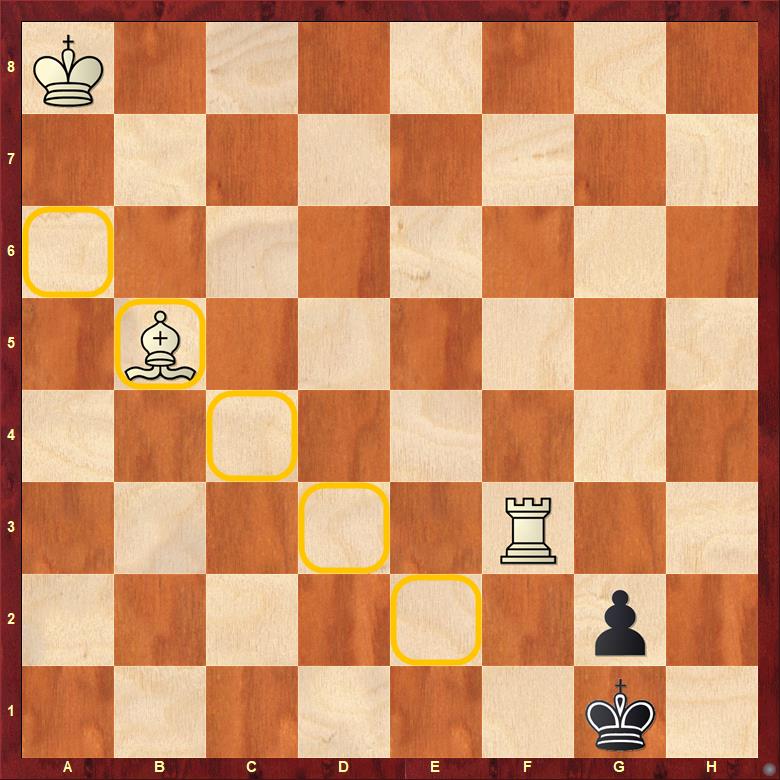

7A.

Our solution is 1…Kh2 but both 1…Kh4 and 1…Kg4 draw.

Q8) Can we eliminate these two cooks?

8A.

With Kf5, the two cooks are eliminated. Note that Kf4 would fail since both Rf3+ and Bd7+ would win.

Q9) What was White's last move?

The rook had to come from the f-file, but it must also stop the dual Bf1, so the rook had to stand on f1.

9A.

Q10) What was Black’s last move?

Clearly, 1…g3-g2.

10A.

Q11) What was White’s last move?

There is no unique last move for White. Most moves by the rook or bishop would win. We reached the end of variation A. The solution for study A is 1…g2 2.Rf3+ Kh2 or Kh4 3.Bf1 g1Q 4.Rh3 mate. Now we explore option B from diagram 7.

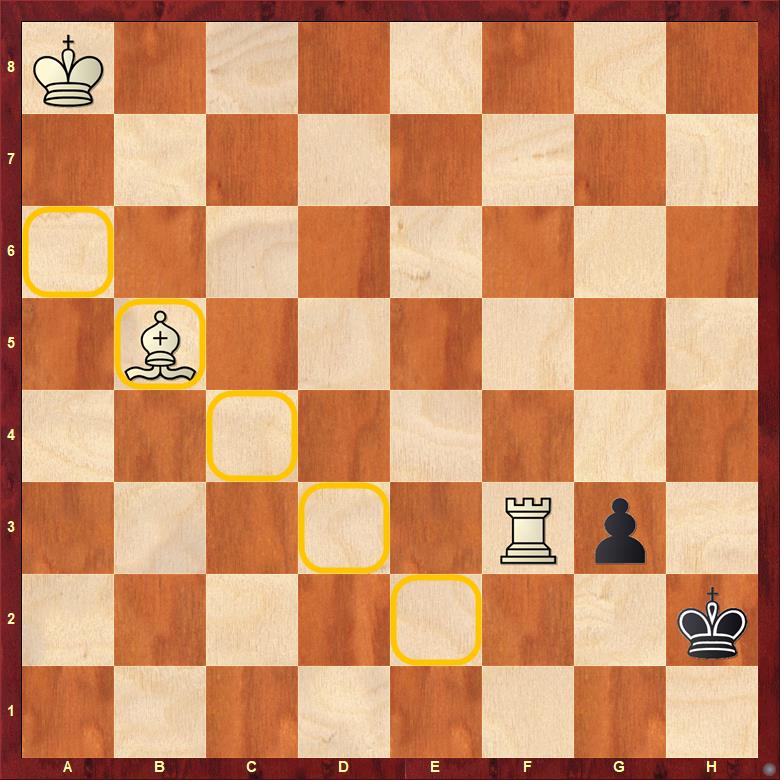

7B.

1…Kh2 2.Bf1 is our solution and 1…Kh1 2.Bc6 wins.

Q12) What was White’s last move?

Try various arrangements, but the only one that works is:

8B.

1.Be2 Kh2 1…Kh1 2.Rh3+ Kg1 3.Bf3 2.Bf1 g1Q 3.Rh3 mate.

Q13) What was Black's last move?

The only possibility that avoids a cook is 1…g2.

9B.

1…Kh2 and 1…g2 are answered by 2.Be2

Q14) What was White’s last move?

There is none. So the solution of study B is 1…g2 2.Be2 Kh2 3.Bf1 g1Q 4.Rh3 mate.

On to variation C.

7C.

Now we examine option C with 1…g3-g2.

8C.

Q15) What was White’s last move?

White could have moved with rook or bishop. If White’s last move was with the rook, we need to exclude the dual Bf1 and Bc6.

Q16) How can we accomplish that?

9C.

Rf1 and Kc6 stop the two duals. Other arrangements of the white king and bishop are possible such as moving the king to d5.

Q17) What was Black’s last move?

1...g3 was the last move.

Q18) What was White’s last move?

No prior move for White is possible. If you solved through Diagram 9C, you did as well as Richard Reti who published this study in the newspaper Bohemia, in 1923.

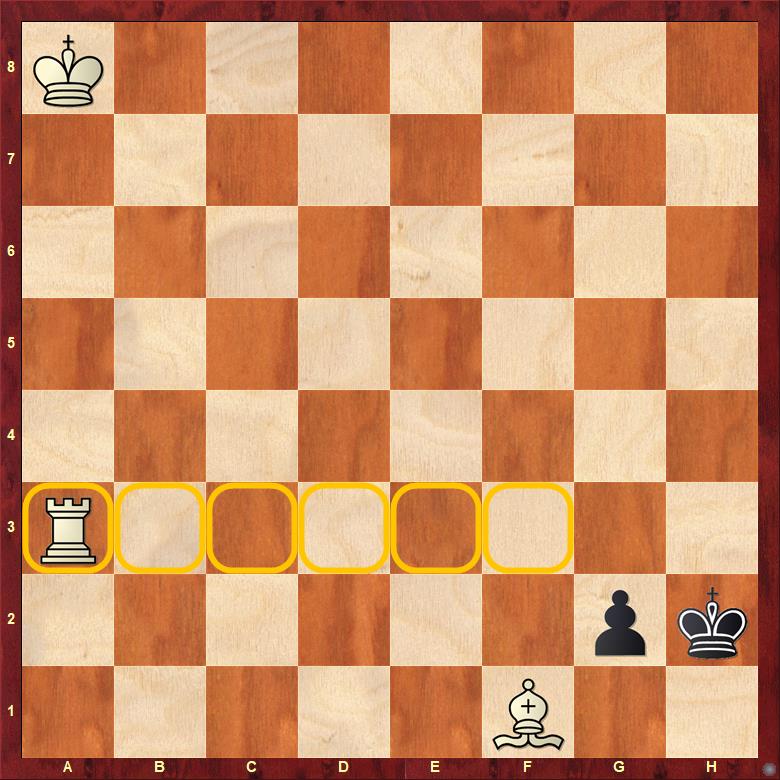

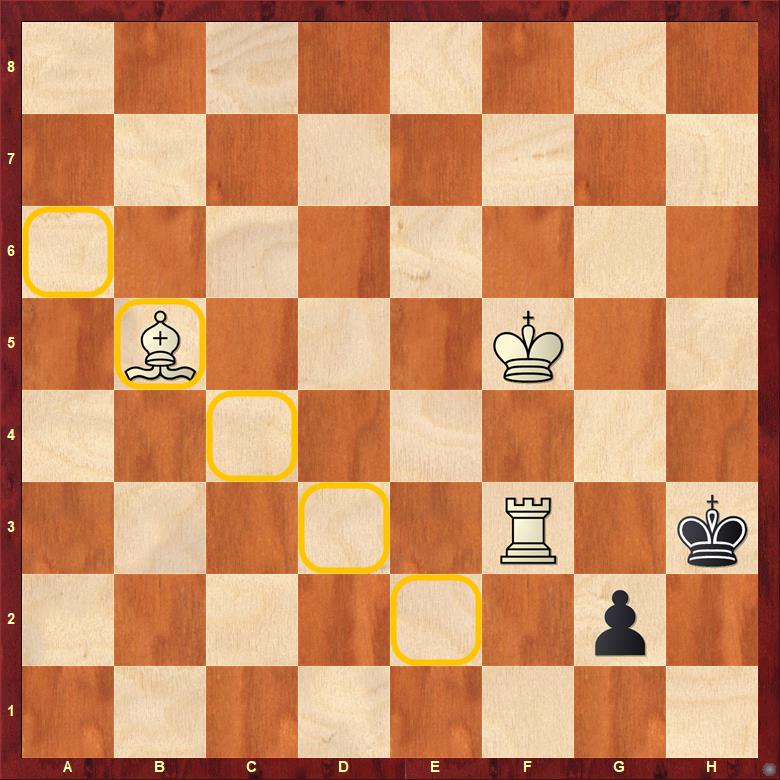

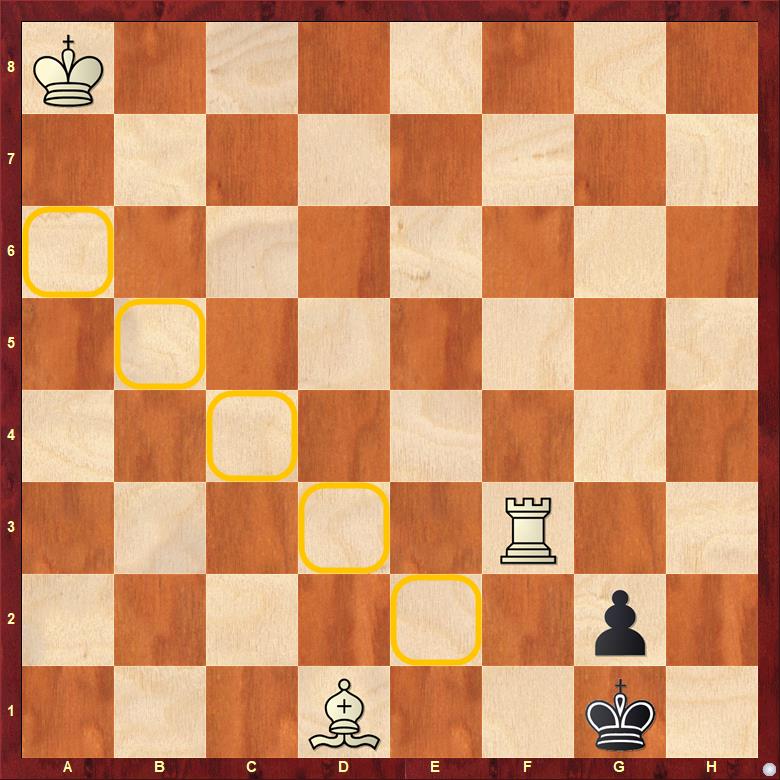

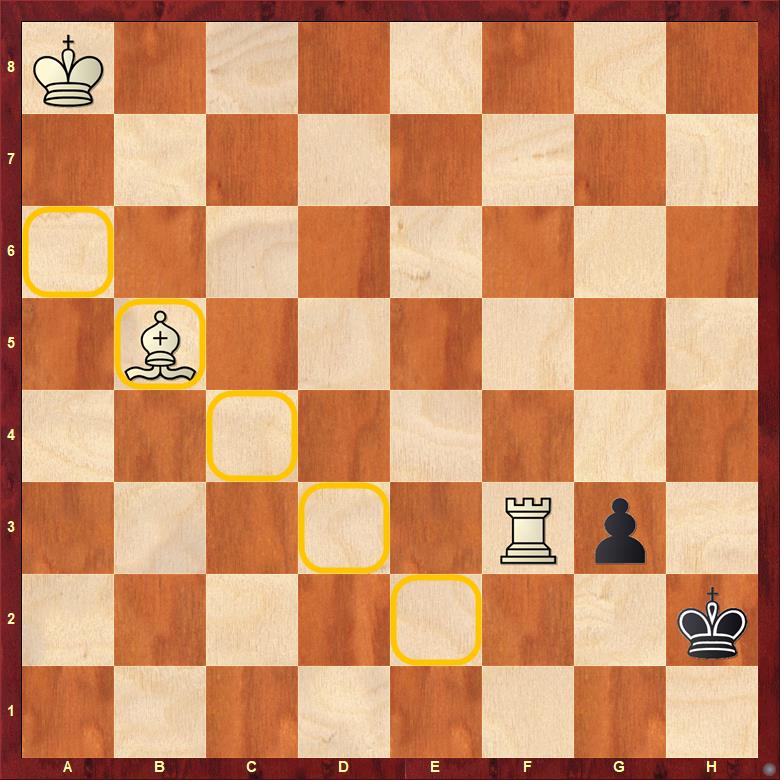

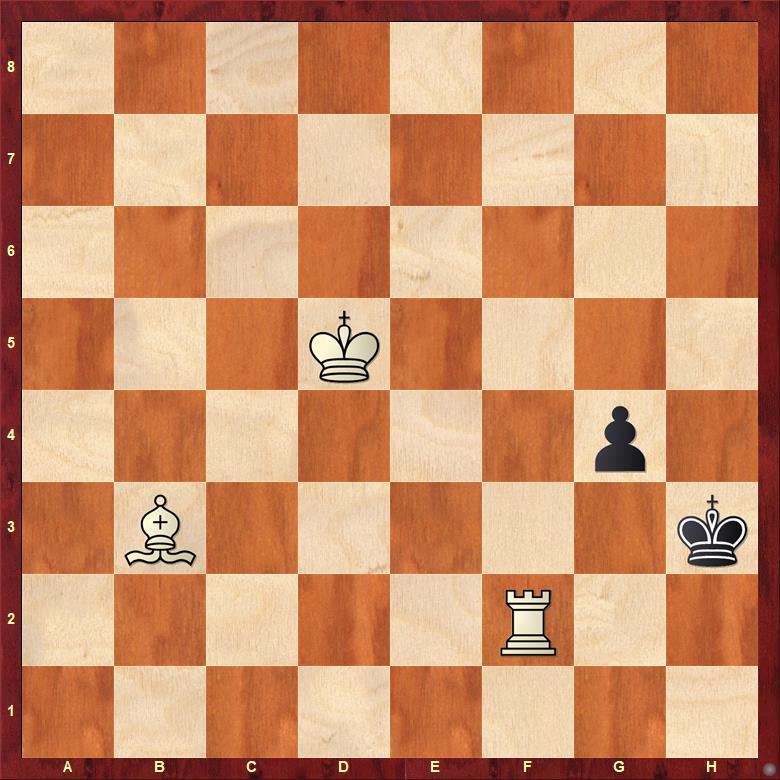

8D.

In diagram 8C, we assumed that White’s last move was with the rook. If White’s last move was with the bishop, we again must stop the Bc6 dual and preclude Bf1.

Q19) How can we do this?

9D.

With Ba4 everything is resolved.

Q20) What was Black’s last move?

10D.

1…Kh3-h2 is our desired solution but 1…Kg4 or 1…Kh4 will draw.

Q21) How to remove these cooks?

With the king on d5, 1…Kh4 2.Bd7 or 1…Kg4 2.Ke4! g2 3.Bd7+ wins.

Q22) What was White's last move?

12D.

White’s last move had to be with rook. Starting from f1 allows the duals Rf3, Bd7+, and Ke4. So, the only possible placement is f2, but here both Rf3 and Bd7+ win.

Q23) How can we remove the dual Bd7+?

Bb3 or Ba2, exclude the dual Bd7+.

Q24) What was Black's last move?

Obviously, 1...g3.

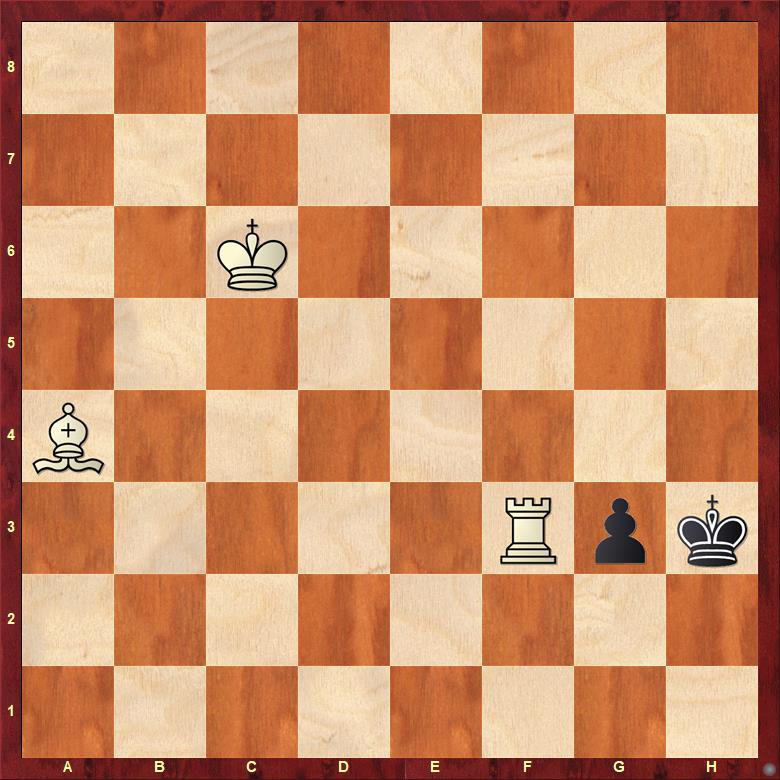

14D.

Q25) What was White’s last move?

White threatens 1.Ke5 and 2.Bd5 winning. To exclude this the rook must be attacked.

15D.

Rf3 or Rh2 would check the black king, making the position illegal. Therefore, Rg2 is the only possibility for a unique move.

Q26) What was Black’s last move?

Obviously, 1…Kh3 is the last move.

Q27) Is there a white move before that?

No. We can’t find prior moves without adding material, so we will stop here.

Solution: 1.Rf2 g3 2.Rf3 Kh2 3.Bc4 g2 4.Bf1 g1Q 5.Rh3 mate.

For the study above, together with Nikolai Kralin, you won 2nd prize from the Bulletin Central Chess Club USSR, 1963. Study D is the best of the four because it is five moves, compared with three moves for the other three studies. Sum up your correct answers and find your composing level:

23-27 Excellent! You are a prize-winning composer – you can get the most impact from any given material.

15-22 Great!

7-14 Promising

0-6 This article is terrible!

About the Author